A miscellany like Grandma’s attic in Taunton, MA or Mission Street's Thrift Town in San Francisco or a Council, ID yard sale in cloudy mid April or a celestial roadmap no one folded—you take your pick.

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

impromptu poem

impromptu poem

the river moon just a few feet from the man;

the mast lamp illumines the third watch darkness—

on the sandbank herons rest, folded & silent;

in the boat's wake a fish breaks water, splashes

Jack Hayes

© 2016

based on Du Fu: 漫成一首

màn chéng yī shŏu

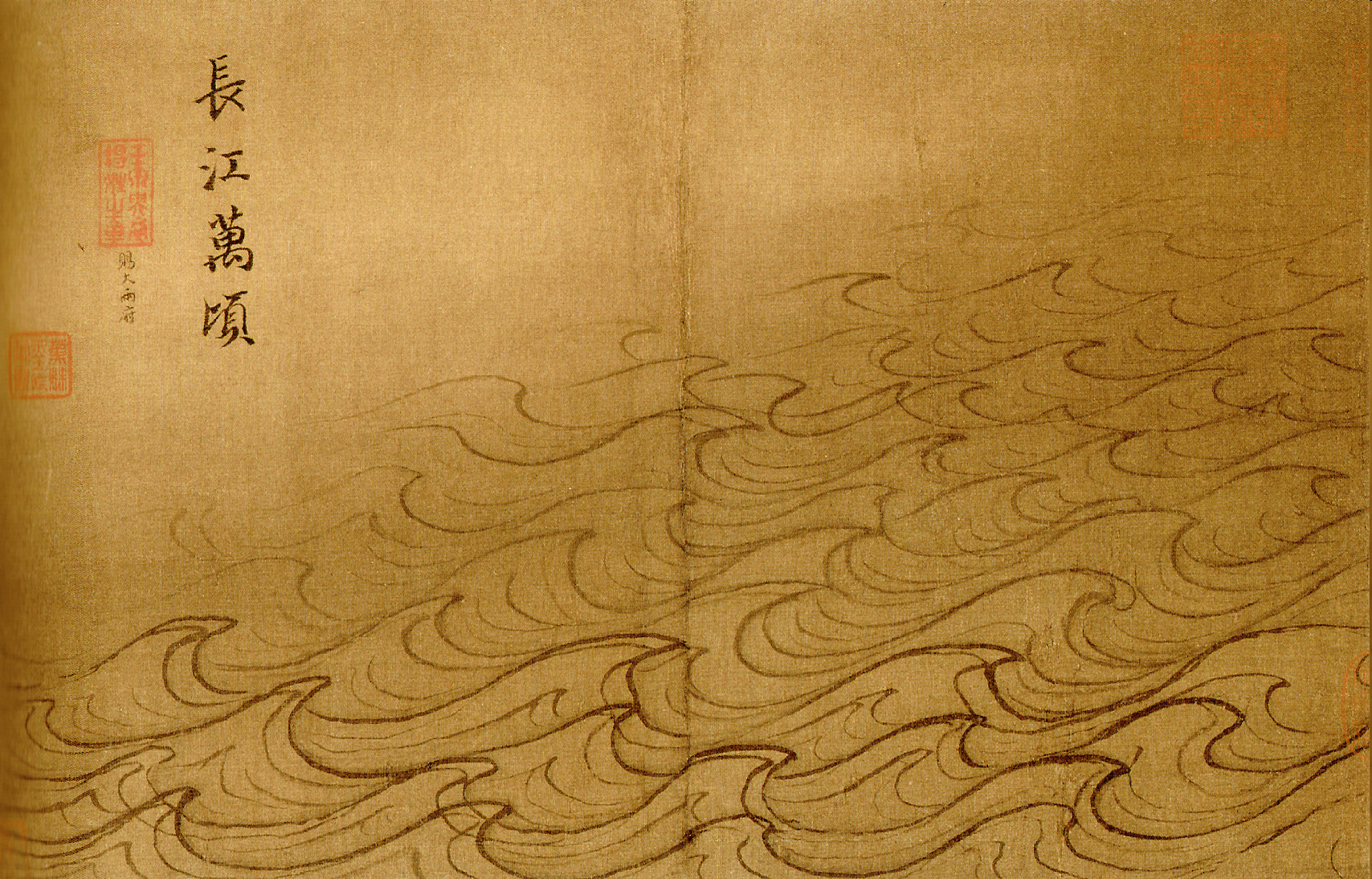

Image links to its source on Wiki Commons:

Ten Thousand Riplets on the Yangzi: Ma Yuan, 1160-1225. Ink on silk.

Public domain

Monday, May 30, 2016

octet for a day made of flowers

blackberry stalks bloom white in a cedar hedge;

with no apparent plan a butterfly darts

into traffic—within wilted rhododendrons

sparrows talk & I can't make it out at all—

that flat gravestone under a pine: another

among the ten thousand things I remember—

ashes ashes where its shadow has fallen—

roses droop overwhelming a chain link fence

Jack Hayes

© 2016

with no apparent plan a butterfly darts

into traffic—within wilted rhododendrons

sparrows talk & I can't make it out at all—

that flat gravestone under a pine: another

among the ten thousand things I remember—

ashes ashes where its shadow has fallen—

roses droop overwhelming a chain link fence

Jack Hayes

© 2016

Saturday, May 28, 2016

new moon cello (after Zoë Keating)

for Sheila

loss is constant across the dimensions:

an entire Chinese bestiary achieving form & gone:

waning crescent moon melting to new moon’s

hollow, this improvisation soaring beyond &

beyond the vanishing point in this theater’s

sapphire light, that flock of

crows rising off a frozen pasture in March, grass

stubble ragged amidst corn snow: faces

taking form & gone—the helicopter blasting

cherry blossoms westward off

boughs in Waterfront Park, that perfect

blue Thursday, sun a halo of

grief: now May, & ghostly

rhododendrons nod—notes swell

& fade & swell & fade, the sinews drawing

pangs travail transcendence across

four strings to that foursquare city built beyond time;

“it’s in the nature of things”—black Willamette

rolling past bridge lights, polyphony rolling past

stage lights now violet now emerald opal amber;

the heart’s daily shattering, blue flowered

saucer dropped to the floor, & the hand reaching out,

holding shards forth: at the continent’s other extreme

you absorbed in a poem where a butterfly disappears

within crimson blossoms: dark cello,

waxing crescent silver hair wave, eyes closed in unlit

night amongst such profusion of quavers our incarnations

brief & brief then brief again

Jack Hayes

© 2016

Thursday, May 26, 2016

octet with pneumonia

that cold March rain's cascade of influenza;

raindrops magnified against a glass bus shelter—

the next bus coughs, kneeling, exhaling all air;

fever one o three living room gone orange—

alveoli collapsed already, heart muscle

aflutter: a blackbird trapped in a chimney—

an oxygen concentrator's ghost breaths count

night's moments—as if daybreak's birds may yet fly

Jack Hayes

© 2016

raindrops magnified against a glass bus shelter—

the next bus coughs, kneeling, exhaling all air;

fever one o three living room gone orange—

alveoli collapsed already, heart muscle

aflutter: a blackbird trapped in a chimney—

an oxygen concentrator's ghost breaths count

night's moments—as if daybreak's birds may yet fly

Jack Hayes

© 2016

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Crooked River

Crooked River

#1

each blossom petal that falls diminishes Spring;

with ten thousand swirled in the wind, a man must worry—

yet I watch with longing till the last petal passes from sight,

as I won’t begrudge myself ale, however it sickens me—

in the small river pavilion, green kingfishers nest;

by the park’s great mausoleum, qilin crouch—

each atom of natural law impels us toward joy:

what good is fleeting fame but to hinder these bodies?

#2

daily returning from morning court I pawn spring clothes;

each evening I come back from the riverside drunk—

everywhere I go, I owe money for ale;

but it’s rare for a man to approach his 70 years—

penetrating blossoms’ depths, butterflies appear;

dragonflies at leisure skim over the water—

the wind & light proclaim flow & shift as one:

why should we not enjoy time’s brief passage?

Jack Hayes

© 2016

based on Du Fu: 曲江二首

qū jiāng

Notes:

The 曲江 or qū jiāng is variously translated as “Meandering River”, “Winding River”, “Twisting River”, Serpentine River”, & “Curved River”. I chose the word “Crooked” not to be contrarian, but because another sense of 曲 is “wrong.”

There’s a fine discussion of the Serpentine River Park in Charles Benn’s China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. I’ve excerpted portions that are relevant:

Several parks existed in the districts outside the Forbidden Park and the palaces. The greatest of them was Serpentine River in the southeast corner of the city. In the early eighth century the throne had the river flowing through the area dredged to form a lake so deep that one could not see the bottom. It was joined to a much older park called the Lotus Garden. In 756 it became the most popular spot for feasts the emperors bestowed upon officials [note: the poem is dated to 758]…. The Serpentine River and Lotus Garden had willows, poplars, lotus, chrysanthemums, marsh grasses and reeds…. Patricians could visit the Serpentine River at any time of the year, but they were especially fond of going there during the spring.

Benn, Charles. China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, pg. 68

qilin: The qilin is often translated as “Chinese Unicorn”, though they are very different from the unicorns of European myth & legend. In fact, qilin are often depicted as having antlers rather than a single horn. Depictions of the creature varied at different points in history, but it's often a chimera-like being, combining aspects of different animals. They were considered good omens of prosperity & serenity. Interestingly, a giraffe that was brought to the Ming Dynasty court was thought to be a qilin! One other note: in the standard pinyin Romanization, the “q” is pronounced like the “ch” in “church”.

"hinder these bodies": (絆此身 bàn cǐ shēn) The 身shēn character can refer not only to the body of a human or animal, but also to one's moral character; it is also used to refer to a world in Buddhism. Sheila linked this to the doctrine of Trikaya, which refers to the three bodies of the Buddha. In later Chan Buddhism (i.e., by the Song Dynasty) a direct link was made between the Buddha bodies & the body (or bodies) of the practitioner:

The Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu advises:

Do you wish to be not different from the Buddhas and patriarchs? Then just do not look for anything outside. The pure light of your own heart [i.e., 心, mind] at this instant is the Dharmakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-differentiating light of your heart at this instant is the Sambhogakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-discriminating light of your own heart at this instant is the Nirmanakaya Buddha in your own house. This trinity of the Buddha's body is none other than he here before your eyes, listening to my expounding the Dharma.

At this point I'm unable to confirm that this specific mode of thinking would have been current in Du Fu's own day, though Chan Buddhism was certainly developing during the Tang Dynasty, & Du Fu had close relationships with various Buddhist monks as evidenced by a number of his poems.

Image links to its source on Wiki Commons:Qing dynasty qilin: Bronze sculpture located at the New Imperial Summer Palace. Picture taken late September 2002 by Leonard G. who makes it available under the Creative Commons ShareAlike 1.0 License.

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

Translating Li Bai’s Cháng’àn Xíng (Chang'an Ballad)

The poet should always recognize his complete audacity when venturing into the realm of translation, & venturing to translate Li Bai's great poem 長干行 (Cháng’àn Xíng) is doubly audacious, because one is dealing not only with the great original, but also Ezra Pound's justifiably famous version, "The River-Merchant's Wife: a Letter". But after some debate, my translation partner Sheila Graham-Smith & I have rushed in where angels fear to tread. You can see the result here.

To say that Classical Chinese presents challenges to the translator is an understatement. It’s difficult enough to render a French, or Latin, or German poem into English, & English is directly related to all three of those languages. There are problems of nuance & expression that arise constantly. But Classical Chinese is a much different situation. While there are important differences between all European languages, & especially between the Romance & Germanic languages (of which English is a hybrid), Classical Chinese (& Mandarin as well) really presents a whole new set of problems that go far beyond nuance. Classical Chinese poems are telegraphic in the extreme; there’s no conjugation of verbs, declension of nouns, pronouns are for the most part absent, word order is not fixed in the way we’re used to (& indeed, word order of Classical Chinese poetry is much more fluid than word order of Classical Chinese prose) & any number of markers that could guide a person through a sentence of French or Latin simply don’t exist on the page. By way of illustration, here is a simplified word-for-word translation of the first six lines of the poem (remembering that a number of these words have multiple possible meanings:

I, your servant develop at first cover forehead

break off blossom gate in front play

boy ride horseback bamboo horse arrive

surround bench play with green plums

together dwell Chang’an inside

two small not have suspicion misgivings

Sheila & I have developed a process for our translations. Once a poem is chosen, I make a literal crib of the characters—but I try to find all the nuances of meaning in the first go-round rather than limiting each character to its most likely meaning. I also find all the existing English language versions of a given poem I can (& also other English language cribs, if they are available), & review them carefully. At what points do they seem to diverge from the meanings I’ve derived from my crib? Do a number of translations (especially among the more reliable translators) all diverge at this same point? At what points are the translations weak as English language poems, & at what points are they strong. I remain of the opinion that one needs to strive to produce the best English language poem possible within the framework of the translation’s determined meaning. If we are going to interest readers in the great poets of another language, how are we going to do so with bad English verse? This is why Pound’s version of Cháng’àn Xíng, for all its errors in translating Chinese to English, is far better than a more accurate version that’s insipid poetry. Pound made mistakes—even some fairly big mistakes—but if you read his poem, you will want to find out more about Li Bai. This is certainly not true for many versions!

Once I’ve compiled the crib & other versions, I work on a draft & attempt to polish that as well as I can before sending it, along with everything else from the poem in Chinese to English versions to cribs to Sheila for editing & research. Depending on the complexity of the issues involved, there may be a number of subsequent exchanges before we settle on a final version.

Now to turn to some specifics. One of the great debates about Cháng’àn Xíng has to do with the speaker’s tone, especially in the poem’s concluding lines. There are some who believe that she is saying she will go as far as Changfengsha but not a step further; others, myself included, believe the tone to be tender & deferential throughout, & I’ve tried to convey that as well as I can. Indeed, the poem’s first character, 妾 or Qiè, can be translated as “I, your concubine”, or “I, your servant”. It’s a word that indicates deference by a woman to a man. However, the most reliable sources all agree that to translate it literally calls too much attention in English to an expression that would be natural in Chinese. Such deference is assumed, whereas in English it would be read either as an unnatural submission or an exotic expression of humility, or both, & the point would be missed. This same character appears again in line 25. I have tried to indicate some of this deference not only in the general tone, but also in my version of line 7: “at fourteen I became, my lord, your wife”; Pound, in one of his more inspired moves, translated this as “At fourteen I married My Lord you.”

But back to Changfengsha. No less a translator than David Hinton renders the ending as “I’m not saying I’d go far to meet you,/no further than Ch’ang-feng Sands.” There is also the problem of the line about the letter immediately preceding this. Why does she ask him to write a letter? Indeed, the line can come across as being imperious, though I don’t believe for a moment that’s Li Bai’s intent. A literal crib of the final four lines might read:

sooner or later to go down three Ba

in advance do letter tell home

together greet not to speak of distance

all the way arrive Changfengsa

San Ba ( sometimes translated as the Three Bas) was a district in Tang Dynasty China in what is now eastern Sichuan; Changfengsha is literally “Long Wind Sands”, & some translate the place name. Interestingly, 巴 means among other things “sorrow”, & if one wanted to take a risk in translating, rendering the San Ba into the Three Sorrows would potentially add to the poem’s meaning. We considered this possibility, but decided we wanted to keep the place names in Chinese—if we translated San Ba, why not translate Chang’an to “Eternal Peace”?

This also raises the point of the conditionality strongly implied in the San Ba line. Is she saying “when you sail back through San Ba” or “if you sail back through San Ba”. This is just the sort of thing that tends not to be explicit in Classical Chinese poetry. We debated this point for a long time. My inclination at one point was to follow the example of Arthur Sze & Jun Tang, who in his paper titled "Ezra Pound’s The River Merchant’s Wife: Representations of a Decontextualized “Chineseness”" & use “if; it seemed to me that "if" softens the request for a letter in the following line.

But I've changed my thinking on this. First, it seems certain that his return journey would take him through San Ba, so why would she say "if"? Then why would she request a letter? Because she isn't waiting for him to get home—she's so eager for his return that she wants to meet him on the way. How else would she know when to expect him in Changfengsha? In any case, my somewhat archaic use of “do” in line 28 is intended to convey tenderness rather than a demand. I actually use the expression myself, but then, I too am somewhat archaic at this point.

The other crux I’d like to mention comes especially in lines 13-14, though the passage really begins in line 7. A literal reading goes as follows:

Fourteen become my lord wife

shy face not yet experience open

lower head toward dark wall

thousand calls not to be one turn around

fifteen begin to beam with joy

desire together with dust follow ashes

always keep to hold pillar truthful

how go up gaze into the distance husband I?

There are two separate issues here, though the lines certainly present a condensed narrative throughout the passage. First, I take lines 8-11 to specifically address sexual awakening. Generally these lines are translated as having to do with whether she would look at, & more specifically, smile for her husband, but I believe the meaning is more intimate than that, & have translated them to suggest that. In this case I’m going a lot on instinct, but Sheila does agree with me on this point.

Lines 13-14 are more obscure however. Pound essentially sidestepped them, especially line 13, which he combined with line 12 to produce: “I desired my dust to be mingled with yours/Forever and forever and forever.” First, it’s worth noting that Classical Chinese poems typically break into couplets, & as such, line 13 would not follow upon line 12 in the way his version suggests. But more importantly, his version is at best an extremely free rendering of the underlying meaning in line 13, without capturing any of the literal meaning.

Line 13 refers to a legend about one Wei Sheng, who, to quote the online Yabla dictionary was a “legendary character who waited for his love under a bridge until he was drowned in the surging waters”, & by extension, someone “who keeps to their word no matter what”. Most, but not all, translations assign these lines as describing the husband—the speaker believes he will stay as true to her as Wei Sheng did to his love.

Not all translators do this, however—JP Seaton & Arthur Sze both assign the line to the woman—that she has decided to stay true no matter what. Sheila’s research uncovered not only the fact that the Blue Bridge where Wei Sheng drowned has proverbially referred to devoted love in general, whether the love is a man’s or woman’s love, but also that the Wei Sheng story, at least by the late Tang, was a Romeo & Juliet type story in which the woman committed suicide after finding out that Wei Sheng drowned. We can’t say for certain this story was current in the high Tang period when Li Bai was writing, but since it’s attested in a written source not all that long afterward, it does seem likely.

What put Sheila on to exploring this question further was line 14. First, she surmised that the line about climbing something high to look for her husband made no sense if line 13 was about the husband, & it’s hard to argue with her logic. She also found stories of women climbing mountains to look for their men returning & staying to gaze so long they turned into salt. It’s our sense that Li Bai is alluding to such stories in line 14, & as such, they complement the Wei Sheng story in line 13.

There are many issues that could be raised in discussing the impossible but richly absorbing experience of translating Cháng’àn Xíng. I’ve only sketched a few of the main cruxes & already this is an extraordinarily long blog post. But I hope this will inspire some to study the poem, the great Li Bai, & indeed, Classical Chinese poetry more deeply. There are wonders to be found.

A select bibliography of important versions of Cháng’àn Xíng, & other Li Bai poems would include the following:

Cooper, Arthur, Li Po and Tu Fu. New York: Penguin, 1973

Hinton, David, The Selected Poems of Li Po. New York: New Directions, 1996

Holyoak, Keith, Facing the Moon: Poems by Li Bai and Du Fu. Durham: Oyster River, 2015

Pound, Ezra, Cathay. London: Elkin Matthews, 1915

Seaton, J.P., Bright Moon, White Clouds: Selected Poems of Li Po. Boston: Shambala, 2012

Sze, Arthur, The Silk Dragon: Translations from the Chinese. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2001

Waley, Arthur, The Poet Li Po. London: East and West, 1919

The works by Pound & Waley are both in the public domain, & links to them at the Internet Archive & Project Gutenberg respectively are provided. For what it's worth, I like both the Waley & Sze versions quite well.

Image links to its source on Wiki Commons:“Emperor Minghuang, seated on a terrace, observes Li Bai write poetry while having his boots taken off (Qing dynasty illustration)” – 17th century: piblic domain.

Wednesday, May 11, 2016

Chang’an Ballad

Chang’an Ballad

when my hair was scarcely fringed across my brows

I plucked blossoms, playing by the front gate;

you a boy astride a bamboo horse came by,

chasing me round the garden bed, flinging green plums:

together we dwelt in the midst of Chang’an,

two little ones without mistrust or misgivings;

at fourteen I became, my lord, your wife—

bashful, not yet ready to smile for you,

I lowered my head toward the dark wall;

a thousand times you called; not once did I turn—

at fifteen my eyes were opened:

I wished our ashes and dust to mingle at last;

always keeping faith, clinging to the post:

how could I climb on high to watch for my husband?

at sixteen, my lord, you traveled far away,

to the Qutang Gorge & the Yanyu Stone—

in the fifth month the reef is impassible;

the gibbons’ wailing rises to the heavens—

by the gate the hesitant footprints of your leaving

one by one overgrown by the green moss,

the moss so thick it can’t be swept away—

leaves fall in the early autumn wind:

September butterflies flit near;

in pairs they dart through the west garden grass—

seeing them I fall sick at heart;

I sit & fret, my youthful bloom fading—

soon or late, when you sail back through San Ba,

do write a letter home to tell me in time;

& I will go forth to meet you, no matter the distance,

even as far as Changfengsha

Jack Hayes

© 2016

based on Li Bai: 長干行

Cháng’àn Xíng

Image links to its source on Wiki Commons:Tang Dynasty Tomb Painting: Public Domain

Notes & background on “Chang’an Ballad” will appear on Friday.

Monday, May 9, 2016

storied apricot pavilion

storied apricot pavilion

storied apricot was cut to fashion the beams,

fragrant reeds knotted to fashion a cosmos—

are these rafters or the linings of the clouds?

a place apart for writing between the rains

Jack Hayes

© 2016

based on Wang Wei: 文杏館

wén xìng guăn

endlessly storied apricot pavilion

often rises to the height of the sun—

south mountain replenishes the lake;

before looking ahead, repeatedly turn to consider

Sheila Graham-Smith

© 2016

based on Pei Di: 文杏館

wén xìng guăn

Note: Wang Wei collaborated with his friend Pei Di on a collection of 20 paired poems known in English as the Wang River Collection, or the Wheel River Collection or Wheel Rim River Collection (Wangchuan ji; 辋川集). Each poem is a quatrain (a jueju; 絕句) describing a setting on Wang Wei’s country estate in the foothills of the Qinling Mountains, south of Chang’an in what is today Lantian County.

The poems describe various locations around the estate; pavilions, fenced in enclosures, terraces, & the like. It is important to note that the poets elaborated on the details of the actual locations.

Wang’s poems are very well known—he is one of the most famous of the great Tang Dynasty poets. Pei Di’s poetry on the other hand, including his contributions to this collaborative work, is considerably less well known outside of China. To date only one English translation of the entire Wheel River Collection has been done. This was by Jerome Ch’en & Michael Bullock in their collection Poems of Solitude, published in 1960 & now out of print.

Sheila Graham-Smith & I have produced translations of one pair of poems from the sequence, & we hope to do more in between the Du Fu & Li Bai! You can read my versions of two other poems in the sequence here & here.

Image links to its source on Wiki Commons

"Poetic Feeling in a Thatched Pavilion": Wu Zhen, 1347, ink on paper, handscroll.

Public domain.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)